Letters from a clearvoyant

by Hans van Maanen

In his splendid book, Innumeracy, John Allen Paulos comes up with a beautiful scam to swindle gullible investors. A self-proclaimed ‘investment adviser’, Paulos suggests, sends 32 000 potential customers an impressive-looking letter in which he boasts about his computer models, his expertise and his contacts in the trade. With all this inside knowledge, he adds, he can accurately predict the behaviour of any stock. In 16 000 of these letters, he predicts that one such stock will rise, in the other 16 000 he announces that it will fall.

Obviously, he will be right half of the time. Now, if the stock rose, he sends a follow-up letter to the first 16 000, otherwise to the people for whom he had predicted a decline — and he is good enough to add another prediction: half of the group hears that the stock will rise, the other half that it will decline. Whatever happens, 8000 people will now have two correct predictions in a row.

The remainder of the scheme will be clear (but Paulos explains it anyway). To the 8000 lucky ones, the consultant sends out a third prediction, 4000 with an increase, 4000 with a decline. Again, whatever the stock does, 4000 people will now have had three correct predictions. This goes on a few more times until finally, in Paulos’ example, 500 people had as many as six correct ‘predictions’. Now the consultant strikes. These 500 people are reminded of his incredible performance and are told that, after paying $ 500, they will receive a seventh prediction. ‘If they all pay, that’s $ 250 000 for our advisor,’ Paulos adds.

Mail order prophet

We can be quite sure that the consultant then quickly leaves the state, for this is clearly an illegal set-up. Yet there’s one question that Paulos does not address: did the advisor send these last 500 people his final prediction? And what would become of these people?

For an answer, we have to go back in time. Quite a long way, actually. In 1957, thirty years before Paulos’ book appeared, the American television station CBS broadcast the third season of Alfred Hitchcock presents, an equally splendid series of short stories with themes such as murder, manslaughter and swindle. The second episode, aired on October 13, was called ‘Mail order prophet’, and it tells the story of two rather disgruntled accountants, Ronald Grimes and George Benedict. One day, Grimes receives a letter from a ‘J. Cristiani’, who claims to have supernatural powers and to be able to predict the future. Grimes has, for one reason or another, been chosen as sole beneficiary.

Indeed, the first few predictions of Cristiani — an unexpected election result and a boxing championship — come true, and Grimes is intrigued. Benedict tries to warn him, but in vain: after five of Cristiani’s correct predictions, Grimes has already won $ 700. In a subsequent letter Cristiani requires a financial contribution; in return, he’ll make a prediction for the stock market that will make Grimes very rich. Grimes ‘borrows’ $ 15 000 from the company safe to buy shares in a Canadian mine.

Expertly, Hitchcock builds up the suspense. The stock market will close in a few hours, and Grimes hasn’t yet had any news yet. Grimes has prepared a suicide notes and brought his pills — but in the end, the stock goes up, and instead of taking his pills, Grimes triumphantly resigns. You know what’s wrong with you, he says to his colleague: you’re just too skeptical.

Bewildered, Benedict goes in search of the mysterious Cristiani, and soon finds out that the man is now behind bars for fraud. The postal inspector explains Cristiani’s scheme in great detail — just as John Allen Paulos did. ‘But the prophecy came true!’ Benedict protests. Yes, the inspector says, no wonder: when Cristiani got the money from the last 125 suckers, he sent them all one last completely arbitrary prediction for the stock market. If only one of these came true, he would have asked for one final donation and make a run for it. ‘You do not really believe that he could predict the future, do you? Let this be a lesson.’

In the final shot of the episode we see Ronald Grimes, smiling and stretching his legs comfortably on a deck chair.

Foreknowledge

Did Paulos knew about this episode of Alfred Hitchcock presents? Paulos got the idea, he says, when he was chatting idly with some friends and one of them confessed to having spent a lot of money on a useless stock newsletter. ‘He might have said something about how the guy probably just made up his recommendations. We laughed, elaborated a bit, and the idea stuck with me. When I wrote the book, I refined it into the story I wrote. I’m sure some germ of the idea has occurred to many.’

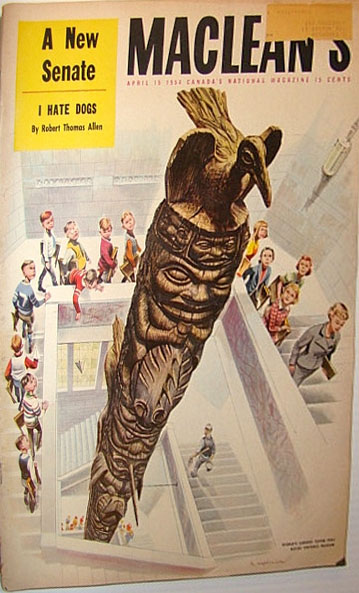

Maclean’s Magazine

Hitchcock’s ‘Mail order prophet’ is based on a story by Canadian journalist and playwright Antony Ferry (1930-1970). Ferry came from London to Canada in World War II, and in the fifties he made a living as a journalist for the Quebec Chronicle-Telegraph, and he wrote a few short stories for Canada’s largest magazine, Maclean’s. On April 15, 1954, it ran his story ‘The strange case of the mail order prophet’.

The main character is called Ronald Gubbins, he is an investment clerk with Peers and Quartz, and he is sucked into Cristiani’s scam masterfully — mayoral elections, boxing match, investing in a mine. The story is as smooth a read as it was in the fifties.

But after his big break, and after putting his money away in four different banks, Gubbins himself starts to investigate the prophet. He goes to the post office, where he is referred to the superintendent. After hearing the name of Cristiani, the superintendent asks how much money Gubbins lost, and then explains Cristiani’s scam.

‘We, ah, of the department have been trying to find out just how much money was lost by the people he took in with his scheme, but unfortunately most of them are reluctant to admit their, ah, gullibility.’

‘Oh, I wasn’t…’

‘Of course, there is no way of forcing anyone to volunteer information, but we are hoping that enough people would be willing to submit to the, ah, rather unfavorable publicity in order to guarantee a conviction.’

‘Oh, no no no, it’s just that I wanted some information about him for personal reasons which I am not at liberty…’

The superintendent watched him with a look of quiet compassion. ‘Ah, yes. I understand, Mr. Gubbins. Quite. Quite.’

Joan Ferry, Antony’s widow, finally managed to locate the story in the crypts of a Canadian university library — at Maclean’s, the old volumes were with the photographer for digitisation, in the Toronto Reference Library, the volume for 1954 seems to be missing.

She remembered talking about the origin of the story with her husband, but he only had mentioned that ‘we talked about it at the newspaper’. She did not know of any earlier sources, and there were no further details in Tony’s diaries from the period. But, she added, thanks to the royalties, they could afford to live comfortably on Mallorca for a year.

Translated from ‘Brieven van een helderziende‘ which appeared in Skepter 27.2 (2015)