Stage Hypnotism Demystified

by Rob Nanninga – original Dutch version in Skepter 7.4 (1994)

Rasti Rostelli attracts capacity audiences with a whirwind show bursting with telekinesis, telepathy and hypnosis. On further investigation the performance turns out to be based on hoary conjuring tricks and the clever selection of suggestible volunteers.

Rasti Rostelli attracts capacity audiences with a whirwind show bursting with telekinesis, telepathy and hypnosis. On further investigation the performance turns out to be based on hoary conjuring tricks and the clever selection of suggestible volunteers.

FOR more than a decade Ronald van den Berg, under the name Rasti Rostelli, has been attracting capacity audiences with his paranormal hypnosis show. It is estimated that the performance is attended by at least a hundred thousand people per year, each of whom forks out 40 guilders for the privilege. Rostelli calls a spade a spade. At the start of his show he openly proclaims “I’m only after your money”.

Despite the high entry-fee the public continues to flood in, for Rostelli pretends to have extraordinary powers. He tells his audience explicitly that he is not a conjuror. Anyone who doesn’t believe him can raise a hand. A girl who still doubts his special abilities is invited on-stage. Rostelli declares he can make her believe anything he wants.

For his first demonstration, he borrows a pack of cigarettes from the audience. He tears out a piece of aluminium foil and pushes it into the girl’s mouth. “Make it good and wet” he orders. Thereafter he folds the wet foil up into a plug, which she must hold firmly in her hand. You have a piece of burning coal in your hand. It is red-hot. You can’t hold it any more. With a cry of pain, she throws the plug onto the ground. Disconcertedly she reports that it did indeed become “awfully hot”. It seems she cannot resist Rostelli’s suggestions.

Actually, she cannot hold the plug in her hand because it really does become very hot. This was clearly shown during Rostelli’s appearance on a Dutch TV show of Astrid Joosten. In this case, the volunteer picked up the plug after she had thrown it down and handed it to Astrid so that she could feel it. Astrid was surprised to find that it was still hot. It was therefore not mere suggestion.

The high temperature is the result of a chemical reaction. A plug that was recoved from the stage during one of Rostelli’s performances was subjected to examination in one of the laboratories of the Technical University of Eindhoven. A white powder could be seen on the aluminium and this turned out to be aluminium oxide. This clearly shows that Rostelli makes the aluminium oxidize. The reaction, which gives off a lot of heat, can be produced by the action of sodium hydroxide (caustic soda). Many people have this in the kitchen for unblocking stopped sinks.

You can try it yourself by dissolving some sodium hydroxide in a little bit of water. Dip your finger-tip in the solution and wipe it on aluminium foil. The concentrated solution destroys the protective skin which normally covers aluminium. This allows oxygen in the air to come in contact with naked aluminium and it promptly begins to “rust”. Be careful not to get the solution in your eyes and wash your hands thoroughly afterwards.

For another trick, which he has performed for years, Rostelli asks the audience for two large coins. Each is fixed over an eye with a cross of adhesive tape. When a blindfold is put on over this everyone is convinced that he can’t see a thing.

Nonetheless, he succeeds in using an impressive sword to chop in two a lemon held by two nervous volunteers. He scores a perfect bullseye, too, with two daggers and a cross-bow. The explanation is straightforward. Rostelli simply squints under the coins and the blindfold. You can notice that he bends his head backwards in order to see as much as possible.

His demonstration of “mind-over-matter” demands even less. A wooden rod is set on end beside a cola bottle on a table. A volunteer must concentrate on the rod after Rostelli has laid it horizontally on top of the bottle. The tension builds and applause erupts when the rod falls from the bottle. Are exceptional powers at work? No, it is a simple conjuring trick any one of us can do tomorrow.

Split a wooden rod in two and fill a capped tube with thick oil. Hollow the wood out until the tube fits into it and glue the two pieces invisibly together. When the rod is set upright, the liquid flows into the bottom end of the tube. Now lay the rod horizontal on the neck of a bottle.

After some time the rod is no longer in balance because the syrupy liquid slowly flows away from the end. The centre of gravity shifts and the rod falls. For the best effect use a metal ball in the liquid and mount the tube a little bit squint.

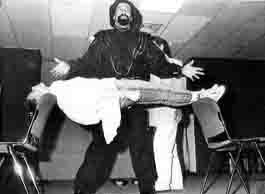

In the second part of the show, Rostelli displays his ability to transform people into willess puppets. He invites over a hundred young volunteers on-stage and begins to order them about in the manner of an army officer. They must stand upright with feet together and may not move a muscle.

Rostelli leaves them in no doubt about what he expects: “If you don’t listen to me you shouldn’t be here. Do exactly what I say without thinking. Just do it. I won’t bother with you if you don’t cooperate. I concentrate only on those who do their best. The only sound you hear is my voice. My wishes are also your wishes.

After Rostelli has let the volunteers stare at a flickering flame for some ten minutes, he makes the suggestion that their eyelids are becoming steadily heavier. Their eyes should close on the count of ten. They should open them again only when he blows in their faces. With an accompaniment of cosmic synthesizer sounds Rostelli tells his victims that their arms are beginning to float up in the air. About half of them lift their arms while trying to imagine that this is happening by itself. The other half is rapidly cleared from the stage.

A following test is that the successful volunteers have to eat a piece of lemon as if it were a juicy peach. This is not so difficult as it seems, since the lemons are not particularly sour. A stream of people who do not carry out his commands convincingly are continually sent away from the stage. Rostelli’s assistant too helps separate the sheep from the goats. “Open your eyes” she says. But anyone who does this is not allowed to play the game further. The subject should only open his eyes when the master blows on them.

Like other stage hypnotists, Rostelli succeeds because he carefully selects his subjects. Over ninety percent of the public is not usable. Eventually, ten or so people remain over, who do exactly what he says. When he blows on their eyes they wake up. And when he snaps his fingers, they immediately fall asleep again.

“When I wake you up, you will look round and see that everybody in the theatre is naked, even your friends and family.” One at a time the volunteers are tried out. Rostelli pays particular attention to the reactions from the public. If there is someone who arouses too little mirth, he runs the risk of spending the rest of the evening on stage as a sleeping piece of scenery.

Hypnosis is much too big a word for the improvised stage pieces Rostelli lets volunteers carry out. The public believes that the subjects see a theater full of naked people but this isn’t so. One of the stars of the evening admitted after the show was over: “I didn’t see anybody naked. You try to imagine how it is. I had some problems with that. It seems to me that people could see that from my reactions.”

However, to judge from the reactions of the audience, his performance was nevertheless highly convincing. But anybody who visits more than one Rostelli show, gradually begins to see that the subjects react in a stereotyped and predictable manner.

Many people believe that under hypnosis you can do things you normally can’t. Scientific research, however, has shown that almost anything that can be done under hypnosis can also be done without it. A good example is the so-called “human plank”, which was already being demonstrated by hypnotists a hundred years ago. The subject must hold his body rigid while he is laid on the backs of two chairs. His shoulders rest on one chair and his ankles on the other. This stunt can be done just as well without hypnosis. A great deal of strength isn’t needed. If the subject is placed on the seats of the chairs, then someone can even stand upon him.

The most suggestible volunteers obey Rostelli’s commands without thinking. They switch off their own intelligence and become completely absorbed in playing a role. One of them told me later: “You receive an instruction and you accept it without question. You surrender to Rostelli. You let yourself be dominated. And then everything goes automatically.”

When the ball begins to roll, there is no way back. If you have said A, you must also say B because Rostelli and the audience are waiting to hear it. Some people begin to enjoy it and let themselves go totally. They try to out-act each other and reep the success of doing so.

Because they are “under hypnosis”, they can unashamedly act as puppets. They don’t need to be afraid of justifying their actions afterwards because their friends and relatives believe they had no control over what they did.

There are those who declare that they are unable to remember what they did on stage. This mostly comes about because they don’t want to remember. I spoke to one person, for example, who was ashamed that he had appeared as a Chippendale. He admitted that he would rather forget his performance: “I don’t actually want to think about it”.

It is difficult to explain to your girlfriend why you did everything Rostelli said. To avoid her tricky questions it is best to stick to the story that you can’t remember.

This is not to say that the volunteers deliberately mislead the public. The most talented volunteers succeed in convincing themselves that everything happened without their own will. They not only do “as if” but begin to believe it themselves. This works best for people with a good imagination. Hypnosis is in fact a method to encourage people to imagine experiences suggested by the hypnotist. Someone who totally succeeds in absorbing himself in this fantasy world can temporarily lose his hold on reality.

One of Rostelli’s most successful subjects told me: “If I read a good book I forget everything around me. It seems that I talk, too, while I am reading. I notice that only if somebody says something about it. I can imagine things easily. If somebody says “egg head”, for example, I have to laugh because I see it immediately. I teach at an elementary school and I sometimes tell the children stories that I make up on the spot. I can do that well.”

Two or three percent of the population have a particularly vivid fantasy life. Their daydreams develop without effort and sometimes seem totally real. When somebody else describes a situation, too, they can see it happening. It is not surprising that these people are particularly easy to “hypnotize” because they are then expected to do things which they are normally good at.

The spectators, furthermore, allow themselves to be convinced that they are witnesses of telepathy and telekinesis but they are only duped. Rostelli does not produce wonders. The only wonder is that the spectators are prepared to pay 40 guilders for a third rate conjuring show.

Translated by Brian Millar from the Dutch original (“Rastelli ontmaskerd“) which was published in De Volkskrant and Skepter 7.4 (1994)