TO THE MEMORY OF

SARAH,

WIFE OF W. MORLEY,

WHO DIED

MAY 24 1902,

AGED 72 YEARS.

The small stone says:

S. M. 1902

Photo: Susan Annear

The case of the death of Sarah Morley rests on two

sources: a newspaper report based on the inquest,

and an article in the British Medical Journal.

Norwich Mercury – Saturday 31 May 1902

(Comments are below the article)

page 8, column 7.

WOMAN BURNT TO DEATH

AT WILTON.

A painful sensation was caused in Wilton on

Saturday morning when it was discovered that a

woman had been burned to death in her house.

Mrs. Sarah Morley was the widow of the late Mr.

William Morley,and seems to have lived a most

unhappy life. She was strongly addicted to

drink. As several men were passing the house on

Saturday morning they noticed a peculiar smell,

but proceeded to their work without further in-

vestigation. P.-c. Barrett passing about 7.15 a.m.

noticed the windows and curtains were black, and

that the front room was full of smoke. He broke

a pane of glass and opened the window, and effected

an entrance. Some neighbours followed him up-

stairs, and there they discovered the body of the

woman so terribly burned as to to [sic] almost beyond

recognition. The news rapidly spread, and a

crowd gathered, the whole affair causing a most

painful impression. The Coroner was communi-

cated with, and an inquiry was held the same after-

noon. Mrs. Fred Brown stated that she went into

the house about eight o’clock the previous evening,

when deceased said felt pains in her body.

Witness was asked to get some gin, which she did.

Just before ten o’clock she went in again, and

found the deceased with candle reading a book.

P.-c. Barrett described the finding of the body.

Mark Johnson identified the body as that of his

sister-in-law. The foreman of the jury, Mr.

Henry Bell, remarked that it was a distressing

case, and there was certain amount of mystery

about it, for no one knew how the body was

burned. The jury returned a verdict “Found

burned, accelerated through drinking.”

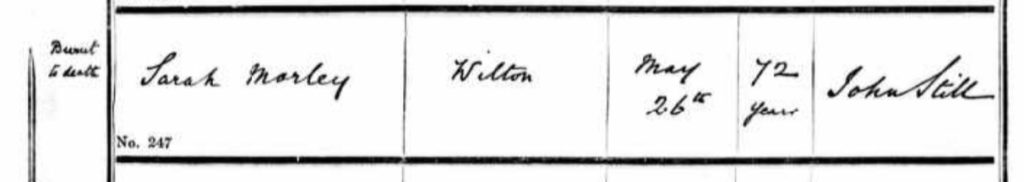

The remains were interred in Wilton churchyard

on Monday afternoon, the Rector (Rev. J. Still)

officiating. Amongst those present were—Mr.

Fuller Rolfe (brother), Mrs. Mark Johnson, Mrs.

Harry Johnson (sisters), Mrs. Tuck and Miss

Rolfe (nieces). Mr. Mark Johnson, Mr. Harry

Johnson, Mr. Tuck, Mr. and Mrs. Watson, Mrs.

Hutt, Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Hicks, Mrs. Gates, &c.

The deceased was in her 73rd year.

Comments on this newspaper article:

The event happened in the night of Friday 23 May to

Saturday 24 May 1901.

‘Wilton’ is part of Hockwold cum Wilton, a village

between Feltwell and Brandon, with then about 600 inhabitants.

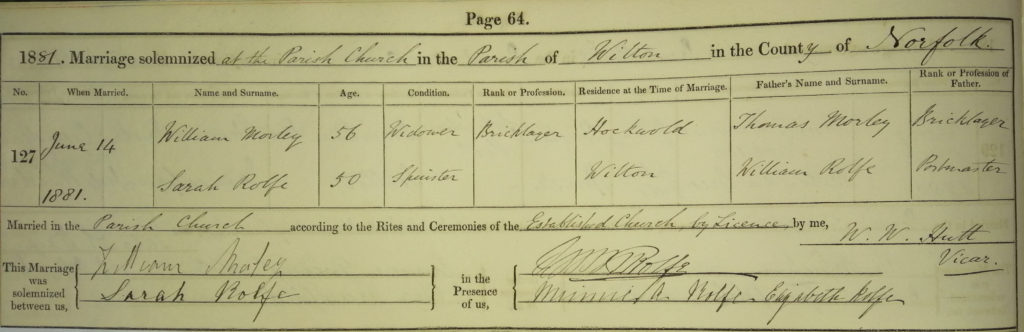

Sarah Morley, was born Sarah Rolfe in 1830. She married

William Morley in 1881, after William’s second wife died in 1880.

Apparently it was her first marriage. The marriage was ‘by Licence’,

i.e. no banns were read.

Photo: Susan Annear. Click to enlarge.

Mrs. Fred Brown is Sarah A. Brown, a neighbor of Sarah Morley.

Albert Barrett was the local police constable.

Henry Bell was the local rate tax collector.

Fuller Rolfe lived in Hertford, about 80 km southwest of Hockwold cum Wilton.

Among his five daughters were Ethel (who was then still living at home) and

Minnie Ann, who had married a Mr. Tuck. She might be the Minnie Ann Rolfe

on the wedding register (and Elizabeth Rolfe her sister). However, Fuller’s

wife was also called Minnie Ann.

Sarah’s sisters at the funeral were Emily and Martha Matilda, married

to respectively the full cousins Mark and Harry Johnson. James and

Clarissa Watson were the local schoolteacher and his wife.

Mrs. Hutt at the funeral was probably the widow Mary B.E. Hutt of

the former Vicar of Wilton (see marriage register),

whose unmarried daughter lived close to Sarah Morley.

Mrs. Smith and Mrs. Hicks were probably from the village.

In 1901 there were four ‘Mrs. Hicks’. But in that year there

was no Mrs. Gates in Hockwold cum Wilton.

Conspicuously absent from this list were William’s son Robert G. Morley

from his second marriage, and two grandchildren of William living in

Hockwold cum Wilton in 1901 are also not mentioned.

The census of 1901 lists Sarah’s house as having only four rooms.

The location was on Wilton Street (then the name of the street leading

from Hockwold to Wilton). For an impression of what her house might

have looked like, see the first photograph of ‘Hockwold in Sepia’. The

photograph dates from 1912.

Doctor Archer (see below) calls the house small, but in Hockwold cum Wilton

there were several four room houses with seven to nine people living in it.

Correspondence in British Medical Journal, Aug, 26, 1905, vol 2. No. 2330, p. 464.

The reference to the issue of August 12th is to an article

on page 345 that discussed a paper by John Knott in

American Medicine, April 22nd, 1905 on the subject of the

belief in spontaneous human combustion.

The author was Ernest George Archer, born 1848 in Feltwell,

and still practising medicine there in 1902.

SIR, – The article in the BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL of

August 12th on spontaneous combustion recalls to my mind a

case which occurred in my practice a year or two ago, which

in the olden time would certainly have been classed as one of

these cases, and which certainly presented many features

difficult of explanation. The facts were these:

An elderly woman, living in a small house by herself, very

intemperate, and a large consumer of spirits of all kinds, was

last seen alive in the evening, as was often her habit, reading

a magazine by candle light. The following morning early a

policeman passing noticed smoke issuing from the closed

shutters of the sitting-room window, and the house was

broken into. The upper part of the walls and the ceiling of

the room were much scorched, but the furniture in the room

was intact. No trace of the occupant was found at first,

but a small heap of black débris was noticed on the floor in

front of a chair, which was an iron one, and the chintz

cover of which was destroyed. I was sent for, and found this

small heap to consist of the broken calcined bones of a human

body. They were lying in a small pyramid, on top of which

lay the skull. All the bones were completely bleached and

brittle, every particle of soft tissue had been consumed. A

table covered with a baize cloth within 3 ft. of the remains

was not even scorched.

I was not called at the inquest held on this case, but the

jury were very much concerned as to the cause of death, and

from some remarks made to me by the foreman afterwards

there appeared to be a decided opinion that this was a case of

“spontaneous combustion.”

It seems probable that the woman’s clothes caught fire,

but how is one to account for the absolute cremation of a

body in the midst of a sitting room filled with furniture?

I may say the remains were seen with me by a brother practi-

tioner, and we were both agreed that several features of the

case were beyond comprehension. – I am, etc.,

Feltwell, Brandon, Aug. 16th. E. G. ARCHER, M.R.C.S.

Sarah Morley’s grave (pictured above) is near St. James church in

Hockwold cum Wilton. It is under a large yew tree, pictured below.

The case appeared in W.G. Aitchison Robertson,

Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, Toxicology and Public

Health (Edinburgh,1908) on p. 116-117.

A case which seems to fulfil all the usual conditions of

spontaneous combustion was related in the medical papers some

months ago. An elderly, very intemperate woman, who lived

alone, was last observed alive reading a paper by candle light;

next morning smoke was seen issuing from the closed shutters

of her sitting-room. On breaking into the house, the upper

part of the walls and ceiling of the room were much scorched,

but the furniture was intact; at first no trace of the occupant

could be found, but a small heap of black debris was noticed

on the floor; this heap consisted of the broken calcined bones

of a human body, with the skull on the top. Every particle

of soft tissue of the body had disappeared, and yet a table

covered with a baize cloth within 3 feet of the remains was

unharmed. The jury were decidedly of the opinion that this

was a case of spontaneous combustion.

The same case was referenced in: J. Dixon Mann, Forensic

Medicine and Toxicology, 6th ed., London, 1922 (p. 216)

as follows:

A typical instance of preternatural combustibility is related

by Archer [footnote] An elderly woman of very intemperate habits, who was a large

consumer of spirits of all kinds, lived alone in a small house. One morning,

smoke was seen issuing from the closed shutters of her sitting-room, and,

on breaking into the house, a small pyramidal heap of broken, calcined human

bones, on the top of which was a skull, was found on the floor in front of a chair

All the bones were completely bleached and brittle, every particle of soft

tissue had been consumed, and yet a table covered with a baize cloth, within

three feet of the remains, was not even scorched; the rest of the furniture in

the room was also intact. It is significant that the ceiling and the upper part

of the walls of the room were scorched, evidently the result of flame.

Footnote: Brit. Med. Journ. 1905.

A further simplification of the story is in

Charles Hoy Fort, Lo! New York, 1931, p. 173 (chapter 14).

… See Dr. Dixon Mann’s Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (edition of 1922)

p. 216). Here, cases are told of and are accepted as veritable – such as

the case of a woman, consumed so by fire that on the floor of her room

there was only a pile of calcined bones left of her. The fire, if in an

ordinary sense it was fire, must have been of the intensity of a furnace:

but a table cloth, only three feet from the pile of cinders, was unscorched.

This 1931 edition of Lo! was further annotated (1997) by X, see

http://www.resologist.net/loei.htm

X adds footnotes to both Mann and Archer.

However, in 1976 Michael Harrison published Fire from Heaven, in which he

expanded this Fort story into a 630 word horror story (starting on page 61) about a Mrs. Euphemia Johnson (68)

in Sydenham (London) in 1922 who was instantly turned into ashes after a sip of freshly

made tea, without her clothes being damaged at all. Needless to say, no such Euphemia

Johnson existed (courtesy Matt Mills). Harrison merely quotes Fort as follows.

“consumed so by fire that on the floor of her room

there was only a pile of calcinated bones … . The fire, if in an

ordinary sense it was fire, must have been of the intensity of a fur-

nace …” (Harrison’s quotation marks, ellipses and italics, note ‘calcinated’

instead of ‘calcined’).

Note that Harrison’s date derives from Fort, without considering that a

1922 handbook might not describe a case of 1922.

Larry E. Arnold, Ablaze! (1995, New York) discusses Archer’s report

extensively on p. 61-62 and quoting ‘The following morning …

scorched.’ , although replacing ‘chintz’ by ‘chir’s [sic]’. Arnold also

reports about Euphemia Johnson, apparently without noting that this

is the same case.

The Hockwold Village Magazine of April 2021 carries a short

article on this subject on page 12.