Spontaneous Human Confabulation:

Requiem for Phyllis

by Jan Willem Nienhuys <janwillemnienhuys@gmail.com> – Skeptical Inquirer, 25(2), March/April 2001

Examination of an oft-repeated tale of spontaneous human combustion reveals distortions, errors, and mystery mongering.

According to popular books on the unexplained, a young woman burst into flames spontaneously in a crowded discotheque in Soho, London, and burnt to ashes in minutes. This extraordinary event apparently occurred at the end of the 1950s.

According to popular books on the unexplained, a young woman burst into flames spontaneously in a crowded discotheque in Soho, London, and burnt to ashes in minutes. This extraordinary event apparently occurred at the end of the 1950s.

The story of Maybelle Andrews dying such a tragic and mysterious way has appeared in a number of versions. In April 1999 it surfaced in the respectable world of a magazine about the Dutch language (where it caught my attention). The discotheque disaster was mentioned in an article about Dutch words for spontaneous human combustion, or SHC. The inspiration for that article was a 1991 firefighter’s magazine. The story may have appeared reliable because firemen supposedly don’t tell old wives’ tales.

Having investigated the various ways in which this and other similar stories have been reported in books and magazines I can shed light on the tale’s origin.

The Making of a Horror Story

Where does the Maybelle Andrews story come from? In itself it is highly implausible. Just for a start, an adult human body can’t burn within five minutes just like that. Because of the short time involved, it would require a very high temperature, but the total heat of combustion of the human body is such that the effect would be similar to burning ten liters (or quarts) of gasoline within five minutes. The nightclub would have been gutted, and all people present would have died of a combination of lack of oxygen and smoke poisoning.

But the story of Maybelle isn’t unique in the annals of SHC. There is a similar story that dates back to the sad death of Phyllis Newcombe as a consequence of a fire at the ballroom of the Shire Hall in Chelmsford, England, in 1938.

The story about Phyllis’s accident first entered the world outside Essex through an item about the inquest, published in the Daily Telegraph on September 20, 1938. That story was somewhat unclear, because it didn’t mention the date of Phyllis’s death, and paid inordinately much more attention to the fact that the ambulance had taken all of twenty minutes to arrive. This may have given superficial readers the impression that the ambulance was too late to save Phyllis. Prominent in the story was a quote from Coroner L.F. Beccles: ‘From all my experience I have never come a case so very mysterious as this.’

The first author to write about Phyllis was science fiction writer Eric Frank Russell. In the May 1942 issue of Tomorrow, in the section ‘Scientific Fantasy,’ he described all kinds of mysterious deaths, including puzzling fire deaths. Of the latter he summarized nineteen cases (all from 1938 and the first week of 1939) that he had culled from British newspapers. He didn’t mention Phyllis by name:

‘Chelmsford woman burned to death in a dance hall’ was followed by Beccles’s quote. A revised version of Russell’s article was printed in Fate (December 1950), and this was reprinted in March 1955 in the UK edition of Fate. In Fate ‘a dance hall’ was changed to ‘in the middle of a dance hall’ and Beccles’ quote read ‘as mysterious’ rather than ‘so very mysterious.’

In Great World Mysteries Russell (1957) considerably embellished the story. The atmosphere on the dance floor is set by ‘Couples glided around the floor, others chatted and sipped soft drinks,’ the victim (still unnamed) ‘burst into flames bang in the middle of a dance hall’ and the remark is added that the victim didn’t smoke and that she hadn’t been in contact with cigarettes. Russell writes: ‘She roared like a blow-torch and no man could save her.’

This version was probably the source for an article in True (May 1964) by the American writer Allan W. Eckert. He dated the accident on September 20, made the location ’the midst of a crowded dance floor,’ let the poor girl ‘burst into intense blue flames’ (like a blow-torch?), made her crumple silently to the floor, and ‘neither her escort nor other would-be rescuers could extinguish the flames. In minutes she was ashes, unrecognizable as a human being.’ Then Eckert made up the first name ‘Leslie’ for Beccles (and changed the quote again). The article was illustrated by a full page picture of a Marilyn Monroe-esque woman in a sexy pose wrapped in flames.

When I e-mailed Eckert to ask for the source of his story (which I knew originally only through quotes) he e-mailed back that he lost his notes and didn’t even have a copy of his own article.

The creator of the Bermuda Triangle, Vincent Gaddis, combines Eckert’s version (‘bluish flames,’ ‘within minutes a blackened mass of ashes’) with Russell’s Fate article (‘middle of dance floor’). His Beccles quote is a mix of Russell’s and Eckert’s versions. Gaddis plays the scholar by giving the Daily Telegraph reference, but judging from his text he never set eyes on that source.

Maybelle Andrews

Maybelle Andrews appears in a paperback by Emile C. Schurmacher titled Strange Unsolved Mysteries (1967). Schurmacher mentions six cases from Great World Mysteries, but neither Russell nor anyone else is credited.

Some of Schurmacher’s cases are word for word identical to Russell’s, some differ somewhat in wording but not in content, and he seems to mix up Russell’s sources.

The story of Phyllis is transmogrified further. Schurmacher’s version gives the impression that he has seen the Daily Telegraph story, but that he had only Russell’s book on hand when he wrote it up. He doesn’t mention a source at all, and has only ‘October’ as a date. Shop manageress Phyllis Newcombe, age 22 (she ran a confectionery store owned by her father) became typist Maybelle Andrews (19), her fiancé Henry McAusland became Billy Clifford (22), the Shire Hall ballroom became ‘one of London’s Soho nightspots’ and ‘Maybelle’ burst into flames while dancing the watusi. The fire was extinguished by hands and a topcoat, but Maybelle died in the ambulance.

As poignant detail Schurmacher pictures Billy ‘with his burned hands swathed in bandages’ at the inquest. (The Telegraph does mention the fiancé helping to put out the fire but more detailed stories in other, local, newspapers say nothing about his role in extinguishing the fire.) The remarks of the coroner are somewhat expanded, but they start with ‘In all my experience I have never been confronted by a case as fantastic as this’. The coroner’s name is changed to James F. Duncan. Coincidentally both Russell’s Fate article and book mention a burn victim named James Duncan from Ballina Co. Mayo, Ireland in close proximity, opposite column or page.

We can safely assume that no one approximately called Maybelle Andrews died in or near London in 1938, or at the end of the 1950s, as Schurmacher later wrote for Reader’s Digest. A search of the register of births and deaths using various spellings can find no trace of the death of a Maybelle Andrews between the first quarter of 1936 to the last quarter of 1946 or between January 1955 to December 1960. The British investigator Melvin Harris has been looking for Maybelle Andrews as well, and in vain. He also thinks that Maybelle is just Phyllis.

Rhythmic Rotations

The following turn on the wheel of fantasy is by Michael Harrison. In Fire from Heaven (1976) he writes that he takes his story about Phyllis from the Daily Telegraph. He even thanks the newspaper’s librarian for providing him with the article. In his story he combines the blue flames and the ‘blackened mass of ashes’ of Gaddis with the boyfriend who ’tried to beat the flames out with his bare hands’ of Schurmacher. Harrison lets Phyllis die in just two minutes.

The jacket blurb of Harrison’s book mentions three cases to whet the appetites of his readers, and one of them says: ‘Phyllis Newcombe engulfed in blue flames on a dance floor and burned to black ash in minutes.’ Harrison describes the party in the Shire hall as a ‘weekly hop’ (with quotation marks, as if he is taking it from the Telegraph) and he describes the inquest as a contest between a prejudiced coroner and the stand-fast and inquiring father. Harrison quotes Beccles too, but he copies Gaddis, rather than the Daily Telegraph.

Then Harrison discusses the Maybelle case and digresses on the remarkable parallels, even surmising that the mysterious fire from heaven must be attracted to rhythmically rotating movements of dancers!

Ablaze! (1995) by Larry E. Arnold is a 500-page book filled to the brim with an immense cluttered mass of descriptions and conjectures, with confused source references and without index. Arnold also describes the death of Phyllis Newcombe (on page 200-201). He writes as if he knows what was in the Daily Telegraph, but he appears to rely completely on Russell, Eckert and especially Harrison and his numerous distortions, except for the quote of ‘Beecles’ [sic] which is exactly as it is in the Telegraph and in Russell’s 1942 version. However, Arnold also read the local newspapers (The Essex Chronicle of September 2, 1938 and The Essex Weekly News of 2 and 23 September) and expresses puzzlement at the fact that the story there differs so much from Harrison’s. That humans can make things up often seems too fantastic for purveyors of the paranormal.

Maybelle Andrews is mentioned by Arnold as well, now as a case from October 1938. For Maybelle Arnold refers to a personal communication from journalist Harrison, who ‘remembered’ the words of coroner James F. Duncan, coincidentally precisely as Schurmacher rendered them. Six lines down the other James Duncan pops up in Ablaze!, but this remarkable coincidence apparently didn’t ring any alarm bells with Arnold.

And so it goes on. Colin Wilson copies Schurmacher in The Occult (1971), Lynn Picknett (a leading authority on the paranormal’ according to the blurb) copies Harrison in Flights of Fancy? (1987), but locates the Shire Hall in Romford and dates Maybelle in the 1920s. Nigel Blundell summarizes Phyllis and Maybelle in precisely six lines in The Supernatural (1996).

In Mysteries of the Unexplained (1982, published by Reader’s Digest) the tragedy in Chelmsford is also copied from Harrison, with precise references to Gaddis and Eckert. In Strange Stories, Amazing Facts (1976), also published by Reader’s Digest, we find an item written by Schurmacher himself, captioned ‘Strange cases of human incendiary bombs’ and adapted from his own book. Here he dates the event ‘in the late 1950’s’.

In 1967 Schurmacher let Maybelle die on the way to hospital from inhaled smoke, but in 1976 it’s first-degree burns that were fatal even before the flames were out. One wonders why instantaneous death by first-degree burns didn’t graduate from Reader’s Digest into the medical literature.

Spontaneous Human Combustion by Jenny Randles and Peter Hough appeared in 1992. They also mention the cases of Phyllis and Maybelle, and they say that they cribbed the whole story from Harrison. That’s only partly true: their version of Billy Clifford’s testimony is straight out of Strange Stories, Amazing Facts and their date ‘late 50s’ comes from the same uncredited source.

Randles and Hough use the cases of Phyllis and Maybelle to surmise that music and dance can attract dangerous kundalini energy. They do not consider that surely billions of energetic dances have been performed in the twentieth century alone without the dancers bursting into flames.

It was the Dutch translation of the Reader’s Digest 1976 book (lacking any references whatsoever and omitting the first-degree burns) that formed the inspiration for a column in Flevo-alarm of June 1991, the newsletter of the fire brigade of Lelystad, and hence the source of a 1999 discussion in a magazine dedicated to the Dutch language.

The True Story of Phyllis

Reading the local newspapers about the tragedy of Phyllis yields a completely different picture.

The English soccer season started again at the end of August 1938, and the Chelmsford City Football Club played its first match on Saturday, August 27. The C.C. Supporters’ Club organised a dance party for the occasion in the venerable Shire Hall (no ‘weekly hop’ as Harrison imagined).

The mayor of Chelmsford and other town dignitaries graced the festivities. Among the 400 attendees was Phyllis Newcombe and her fiancé Henry McAusland (‘Mack’ to his friends). Phyllis had put on her best dress. It resembled a crinoline, billowing out and sweeping the floor and was made of white tulle with satin underneath and a dark blue waist sash.

When the party was over at midnight, Phyllis and Mack stayed a bit longer to talk and to avoid the rush of the departing revellers, but then they left too. Mack walked a few paces in front of Phyllis, but when he had reached the staircase (the ballroom was at the first floor of the Shire Hall, i.e. second floor in U.S. parlance), about fifteen feet from the ballroom exit, he heard Phyllis scream behind him. He turned around and saw the bottom front of the tulle dress burning very brightly and furiously.

Phyllis ran back to the ballroom, where about twenty people were talking together in small groups. They saw her stumble inside, all ablaze, collapsing in the entrance. Mr. Herbert Jewell, one of C.C.F.C.’s directors, immediately took action, he and five others rushed to the rescue, wrapped her in coats, getting singed eyelashes, eyebrows and cheeks in the process. An ambulance was called, which arrived in twenty minutes, and Phyllis was taken to Chelmsford Hospital. She was diagnosed with serious burns on her legs, arms and chest.

At first she seemed to be making quite good progress (her sister Edna, now living in California, tells of Phyllis drinking champagne) but the wounds became septic, and led to pneumonia. And that soon killed her. Even now, in the era of antibiotics, death due to sepsis is a dreaded result of serious burn wounds. Phyllis died on Thursday, September 15, 1938. The inquest was held on Monday, September 19, 1938 in the same Shire Hall, which had been a Crown Court since 1791.

Immediately after the accident it was conjectured that the dress had caught fire through contact with a cigarette end or a lighted match, thrown down from a higher place above the stairs. But witnesses hadn’t seen anybody there, and moreover Phyllis’s father, George, had been experimenting with the tulle and he had found that it wouldn’t catch fire by contact with a burning cigarette, let alone by a grazing contact such as with a falling cigarette end or by the hem of the dress sweeping over it. It’s nearly impossible to set fire to a piece of cloth with a lighted cigarette.

George Newcombe repeated his test in front of coroner L.F. Beccle (not ‘Beccles’ as reported by the Daily Telegraph and all others). McAusland conjectured that the dress might have acquired extra combustibility from the vapors of a chemical cleaning agent used six weeks earlier, but the coroner didn’t go along with this theory.

A match that would have been forcibly thrown from a higher place (a balcony over the staircase) would probably be out before it reached the floor. Also, Phyllis’s dress caught fire on a spot not directly underneath that balcony. Beccle conjectured that the fire probably was caused by a burning match on the ground.

Now how could a burning match be lying on the ground? I have to do a little guessing here. Smoking was not allowed in the ballroom, but the normal behavior of smokers is to light up as soon as they leave a non-smoking area (they don’t drop many cigarette ends then). They light their cigarettes with a match and extinguish the match, for example with a habitual wrist movement and then drop it unthinkingly. The match will go out immediately when it hits a stone floor.

However, when the match falls on a somewhat softer surface it occasionally stays burning for up to five seconds. The floor at the exit of the ballroom was described by the coroner as made of rubber and a witness testified that a lighted match on the floor could go on burning. If my conjecture is correct, the source of the fire was a match thrown on the floor by someone who walked at most five steps in front of her. Phyllis was an indirect victim of nicotinism.

Beccle asked whether a burnt match was found, but police constable Thorogood stated that he hadn’t found any. He also hadn’t found any cigarettes butts where Phyllis’s dress caught fire.

This isn’t very remarkable. Immediately after the accident there must have been quite a few people passing the spot, coming and going, and an already completely burnt match can easily have been trampled completely, or alternatively, the match can have been displaced as the hem of Phyllis’s dress swept over it. It is a common feature of fires that their precise source can’t be found anymore.

So, even though there is an obvious explanation for the accident, it remains a peculiar coincidence for which there is only indirect proof: the place where the fire was first seen on the dress (in front, near the ground), the fact that given the quick spread of the fire it must have started right there and then, and the fact that the dress could only catch fire by contact with a flame. Coroner Beccle commented: ‘In all my experience I have not met anything so very mysterious as this.’ Both local newspapers gave the same version of the quote.

It stands to reason that I am not the first who has tried to guess what precisely happened. Possibly Phyllis knew too. In the hospital Mack asked if she knew the careless devil that had thrown the cigarette end. She answered: ‘What does it matter as long as I get right again?’ This answer might suggest that she knew what must have happened, but that she was such a sweet person that she didn’t want to say.

Phyllis was buried on Wednesday, September 21. Many people attended, both at the service in the cathedral and at the cemetery itself. The Essex Weekly News reported 60 floral tributes. The accident had been an enormous shock to Phyllis’s parents, who were on a holiday at the beach with Edna and possibly her three brothers too. Mack was killed while serving the RAF as a pilot in 1943. Phyllis’s grave is unmarked, and the official history of Shire Hall describes the incident without mentioning her name.

Fiery Trident from Heaven

The Phyllis case of myth-mongering doesn’t stand alone. During my investigations I stumbled on other ludicrous and demonstrably made-up SHC stories.

Take for example the case of Willem ten Bruik. Russell doesn’t mention him in 1942, but he writes in 1950 that ‘a Dutchman Willy Ten Bruik had been lugged out of his car near Nimegen [sic]. Willy was a cinder. The car was little damaged…’ The source was ‘a translated report taken from an unnamed Dutch paper.’ It’s not clear whether he received the report in April 1938, or whether that was the time of the event. In Russell’s book it is the latter, and he says that it was ‘a datum mailed in 1941’. This is curious because at that time Holland was occupied by the Germans, who were at war with the British (among others) and mail service to the United Kingdom was definitely below standards.

Gaddis takes from an article by Michael MacDougall in the (Newark, N.J.) Sunday Star-Ledger of March 13, 1966 the information that one William Ten Bruik died in a Volkswagen, and that the accident happened on April 7, 1938 in Nijmegen (near the east border of the Netherlands). This is strange for three reasons.

In the first place Ferdinand Porsche’s design for a new type of car was revealed for the first time in the summer of 1938 in New York, and on July 3, 1938, the New York Times coined the word ‘Beetle’ for the car which was then officially known as KdF-Wagen. The first stone for the factory was laid on May 26, 1938, by Hitler himself, but civilian production only started after the World War, and only in 1947 were the first fifty-six Beetles delivered to the Dutch importer.

In the second place the name ten Bruik doesn’t occur in the Netherlands, at least not in telephone books now in use. There are many ’ten Brink’ and a few ‘Bruikman,’ but no ten Bruik. The Dutch word ten suggests a location (like brink which means village square) and Bruik means usage, so by its formation the name is odd.

In the third place investigations by municipal authorities, police and newspapers in the neighborhood of Nijmegen have not found a newspaper story or a registered death that corresponds to this case. These authorities know the story, because every now and then they are questioned about it. The first such question was asked by UFO researcher Philip J. Klass in 1967, who was checking an embellishment of the MacDougall story as told in a UFO book. Ever since then helpful Dutch officials have been searching old newspapers and archives to no avail.

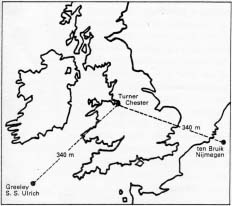

The story of Willem ten Bruik is told in connection with two other burnings in vehicles, one in Upton-by-Chester near Liverpool and the other involved helmsman John Greeley aboard the S.S. Ulrich in the Irish sea. The special thing about these cases was supposed to be that they happened at exactly the same time: 1:14 P.M. in the Irish Sea, 2:14 P.M. in Upton-by-Chester and 3:14 P.M. in Nijmegen, at least that is what the UFO book said. How events presumably known only by their results can be timed so exactly is a miracle in itself.

In Upton-by-Chester the victim was called George Turner. In reality it was Edgar Beattie around 5 P.M. on April 4. The April 7 date belongs to the issue of the Liverpool Echo, the source for Russell’s report on this. In Fate the ten Bruik story follows the Upton-by-Chester report, accompanied by the indication ‘same month, same year’, and that was all MacDougall needed to assert a miraculous coincidence. Schurmacher mentions the Beattie case too (with the Daily Telegraph as reference) but he provides the victim (unnamed by Russell) with the name A.F. Smith. Schurmacher seems to like the middle initial F. This made Harrison point out the remarkable coincidence of two similar accidents on the same spot: another proof of the strange pattern-seeking behavior of the fire from heaven.

Whatever happened in the Irish Sea on April 7, 1938, it can’t have been aboard the S.S. Ulrich, because that ship never existed, as Philip Klass established. Larry Arnold writes that he couldn’t find any deaths of Turner and Greeley in British newspapers around that time.

The simultaneity of these events is also problematic: the Irish Sea has the same time zone as Greenwich, and before WWII Dutch summer time was only 20 minutes ahead of Greenwich, not a full hour.

Harrison exaggerates this story even further. He blames Russell that he missed a curious geographical coincidence related to this triple death. This shows that Harrison reads things in Russell’s work that simply aren’t there, because Russell didn’t mention Greeley or the S.S. Ulrich. Harrison claimed that the three accidents happened at the vertices of a giant equilateral triangle, and that the names of the spots (Ulrich, Upton and Ubbergen near Nijmegen) also start with the same sound.

Then Arnold told Harrison that equilateral triangle wasn’t what the map said. The S.S. Ulrich would have to have been a few miles west of Le Mans for that, deep inside France. Fortean Times editor Bob Rickard made fun of the dubious ‘same sound’ theory. Harrison changed in the next printing equilateral to isosceles, by moving Nijmegen to the south west of the Netherlands, the neighborhood of Antwerp. He remarked that the three names really had the same ‘oo’ sound, because of the dialect near Chester. Unbeknownst to him the Dutch deviously went on pronouncing the first letter of Ubbergen like the ‘ou’ in double or the ‘e’ in butter.

Then Arnold told Harrison that equilateral triangle wasn’t what the map said. The S.S. Ulrich would have to have been a few miles west of Le Mans for that, deep inside France. Fortean Times editor Bob Rickard made fun of the dubious ‘same sound’ theory. Harrison changed in the next printing equilateral to isosceles, by moving Nijmegen to the south west of the Netherlands, the neighborhood of Antwerp. He remarked that the three names really had the same ‘oo’ sound, because of the dialect near Chester. Unbeknownst to him the Dutch deviously went on pronouncing the first letter of Ubbergen like the ‘ou’ in double or the ‘e’ in butter.

I will leave now the discussion of the mysterious trident of fiction that struck Earth on that memorable April 7, 1938.

I wanted to illustrate that whoever tries to investigate or explain stories of spontaneous human combustion (or other tall tales) should take into account that these stories can be distorted enormously, not only by eyewitnesses and newspaper journalists, but foremost by creative writers. They will change many details, leave them out or add them, make up names and dates and moreover they copy each other &150; often without mentioning their sources &150; so the distortions accumulate.

Bookstores are filled with good fiction, and these twisted, illogical, horror stories about so-called miraculous events couldn’t be peddled to the public if the authors didn’t pretend that it all had actually happened.

I see them as ghouls preying on the death and misery of other people to earn money and fame or convert others to their silly superstitions. They should let the dead rest in peace, or rather preserve their memory as they really were.

Acknowledgements

The search for the truth of the Phyllis case has been a joint international effort of many helpful skeptics and others. The author wishes to thank: Mike Ashley, Henriette de Brouwer, Andries Brouwer, Scott Campbell, Edna Conolly (n´e Newcombe), Peter van Dijk, Marcel van Genderen, Mike Hutchinson, Marcel de Jong, C. Kostelijk, Dennis K. Lien, Clare and Ian Martin, Edna Newcombe (sister in law of Phyllis), Joe Nickell, Ed Oomes, H. Rullman, Ranjit Sandhu, Andy Sawyer, Margareth Schroth and Wayne Spencer.

References

The following newspaper stories were used:

Girl in Flames at Shire Hall Dance. The Essex Chronicle, September 2, 1938.

A Human Torch: Chelmsford Woman Badly Burned. The Essex Weekly News, September 2, 1938.

Supporters’ Club Dance. The Essex Weekly News, September 2, 1938.

Death Following Burns: Girl Whose Dress Caught Fire: Tragedy after Dance at Chelmsford. The Essex Weekly News, September 16, 1938.

Young Woman Dies: Burned at Shire Hall Dance. The Essex Chronicle, September 16, 1938.

Girl Burned in Ball Dress: A Coroner’s “Most Mysterious Case: Town in Need of Official Ambulance. The Daily Telegraph and Morning Post, September 20, 1938.

Unsolved Mystery of Dancer’s Death: Dress Which Burst into Flames: Coroner’s Comments at Chelmsford Inquest. The Essex Weekly News, September 23, 1938.

Deaths, Newcombe & Mr. and Mrs. Geo Newcombe. The Essex Chronicle, September 23, 1938.

Dance Tragedy: Dress Material Experiments at Inquest. The Essex Chronicle, September 23, 1938.

Riddle of the Burning Death (review of Fire from Heaven). The Evening News, February 4, 1978.

Also consulted

Arnold, Larry E. 1995. Ablaze!: The Mysterious Fires of Spontaneous Human Combustion. New York, NY: M. Evans and Co., Inc.

Blundell, Nigel. 1996. Fact or Fiction?: Supernatural. London: Sunburst Books.

Eckert, Allan W. 1964. The Baffling Burning Death. True: The Man’s Magazine, May: 32-33, 104-107, 112.

Gaddis, Vincent H. 1968. Mysterious Fires and Lights. Dell Publishing Co., Inc. (first printing David McKay Co. Inc., 1967).

Harrison, Michael. 1978. Fire from Heaven: A Study of Spontaneous Combustion in Human Beings. New York: Methuen. (First edition Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd. 1976, revised edition Pan Books, London, 1977).

Klass, Philip J. 1974. UFOs Explained. New York, NY: Random House.

Picknett, Lynn. 1987. Flights of Fancy? : 100 years of paranormal experiences. London: Ward Lock Limited.

Pon’s Automobielhandel. 1995. De Volkswagenkroniek. Leusden.

Reader’s Digest. 1976. Strange Stories, Amazing facts: Stories That Are Bizarre, Unusual, Odd, Astonishing, and Often Incredible. Pleasantville, NY: The Reader’s Digest Association.

&150;&150;. 1982. Mysteries of the Unexplained: How Ordinary Men and Women Have Experienced the Strange, the Uncanny and the Incredible. Pleasantville, NY: The Reader’s Digest Association.

Randles, Jenny, and Peter Hough. 1992. Spontaneous Human Combustion. London: Robert Hale.

Rickard, R.J.M. 1976. Review of Fire from Heaven. Fortean Times 16, June: 24-26.

&150;&150;. 1977. Fire from Heaven &150; a critique (of the revised paperback edition). Fortean Times 23, Autumn: 26-28.

Russell, Eric Frank. 1942. Invisible Death. Tomorrow, A Journal for the World Citizen of the New Age, May: 8-11.

&150;&159;. 1950. Invisible Death. Fate 3: 8, December: 4-12.

&150;&150;. 1957. Great World Mysteries. London: Dennis Dobson.

Sanderson, Ivan. 1972. Investigating the unexplained. Englewood Cliffs, NY: Prentice Hall, Inc. Schurmacher, Emile C. 1971. Strange Unsolved Mysteries. New York, NY: Paperback Library, Inc.

Wilson, Colin. 1971. The Occult: A History. New York, NY: Random House.

All sources involving Phyllis Newcombe are reproduced verbatim elsewhere on this site.

An almost identical version of this story appeared in The Skeptic 13: 3&4; this site contains also a Dutch version.