For Dutch version click on flag.

The Mars Effect kept skeptics quite busy for quite some time. One of the amazing things is how easily all kinds of skeptics were fooled and how quickly they launched themselves into investigations without examining properly the source of this effect. Rereading the original articles doesn’t lessen this feeling of amazement.

I have written several articles about this matter. One appeared in Skeptical Inquirer in 1997 and can be found here, and for two others I now give the references and a link.

- Paul Kurtz, Jan Willem Nienhuys, Ranjit Sandu (1997) Is the “Mars Effect” genuine? Journal of Scientific Exploration 11 (1), p, 19-39.

- Jan Willem Nienhuys (1997) Ertels “Mars Effekt”: Anatomie einer Pseudowissenschaft. Skeptiker 10 (3), p.92-98. The German version ‘Anatomie’ was a translation of an English text. This English text has been checked in 2017 and some comments are added.

My reason to come back to this in 2017 is a publication of many letters between Martin Gardner and Marcello Truzzi (Dear Martin / Dear Marcello: Gardner and Truzzi on Skepticism). Gardner considered the originator of the Mars Effect, namely the French psychologist Michel Gauquelin, a crank because he was such an ardent believer in his own nonsensical theory. Gardner compared him (on March 8) to the example of a man who believes that the center of the earth is made of jello – an example due to Freud. Gardner wrote (in a PS to his letter of March 5) what it was all about: ‘He presents nothing but one man’s analysis of one’s man [sic] accumulation of French statistics. … Claims of statistical correlations, to support wild theories, are a dime a dozen.’ Gardner thought that the wave of interest in astrology was the reason that Gauquelin’s books sold so well.

Gardner’s correspondent Marcello Truzzi disagreed strongly. In Truzzi’s journal Zetetic Scholar Gauquelin was listed in the group ‘distinguished consulting editors’, even though Truzzi personally didn’t believe Gauquelin’s claim. On March 21 Gardner gave an example: the claim of a man called J.H. Kenneth that multiples of the number pi (3.1415…) have something to do with gestation times of animals. Kenneth gives hundreds of animal species in support of his claim. No biologist had even bothered to check Kenneth’s data. The Gauquelin case was more of the same. Gardner thought it was bad judgment of Kurtz that skeptical publisher Prometheus in Buffalo had published a book by Gauquelin, with a preface by astronomer Abell.

Who was right? Gardner of Truzzi? Judge for yourself.

The beginning

In 1955 Gauquelin published a book titled L’Influence des Astres. The book contained the results of a great number of statistical investigations into the value of astrology, especially the claims of Choisnard and Krafft. Unsurprisingly the results were that in so far as astrological claims could be checked, they appeared to be worthless. A major part, however, was dedicated to a discovery of Gauquelin himself. He had tried to verify one particular astrological claim, which seemed to check out, at least a little bit.

He had found this claim in a booklet (1945) by the astrologer Léon Lasson. Lasson had said that people in certain occupations relatively more often (or less often) were born just after a characteristic ‘planet’ had risen or had reached its highest point in the sky (in Europe: due south). This was especially the case if those people were prominent in their occupation. I put ‘planet’ in quotes because astrologers consider Sun and Moon also as planets.

He had found this claim in a booklet (1945) by the astrologer Léon Lasson. Lasson had said that people in certain occupations relatively more often (or less often) were born just after a characteristic ‘planet’ had risen or had reached its highest point in the sky (in Europe: due south). This was especially the case if those people were prominent in their occupation. I put ‘planet’ in quotes because astrologers consider Sun and Moon also as planets.

This is a claim that can be checked, and that is what Gauquelin had done. It seemed to be not totally nonsense. Just for checking this he had collected almost 6500 birth data.

A short course houses in astrology

But there were problems. The first problem is the strange definition of ‘just after’.

Here I have to interrupt my story for a short course in astrology. A horoscope is in the first place a sketch of the position of the planets on the astrological zodiac. The picture is a circle that represents the zodiac, in other words the ecliptic, the apparent path of the sun between the constellations in the sky. All planets move also more or less along that path. Not exactly, but the astrologer always takes the point on the zodiac closest to the planet’s true position. More technically: only the longitude in ecliptical coordinates is considered.

Now the ecliptic is a great circle in the sky, so it is cut into two equally large halves by the horizon. One will notice in a horoscope (pieces) of a horizontal line. That’s the horizon. As example I give the horoscope of Gauquelin.

The part above that horizontal line is what one can see of the ecliptic on the moment of birth. If you would make a movie of several horoscopes of people, each born 10 minutes later than the previous one, the whole pattern of planets and colored lines and planetary symbols and the outer rim of zodiacal symbols would rotate clockwise, but the horizontal black lines would be stationary. In the course of a single day the planets hardly move with respect to the stars. After a full day (24 hours) the Sun has moved only one degree counterclockwise with respect to the to the total pattern (the tiny radial lines in the outer rim mark the degrees). One might also say that the Sun returns to its original position, but the pattern is moved forward by one degree. Only the moon moves visibly in a day. The next day it is shifted about 12 degrees counterclockwise, compared to the position on the day before.

Astrologers like to subdivide the parts above and below the horizon further into so-called houses: six above the horizon and six below. This subdivision amounts to subdividing the sky as visible above the horizon at the time of birth into six pieces (and likewise the part of the sky below the horizon). The aim is actually a subdivision of the ecliptic. There are many (roughly 50) ways of doing that. Traditionally the astrologer used the method that was easiest to compute.

One way is the method of Placidus. That’s also the way used in the horoscope pictured here. You’ll notice that the houses are numbered 1 to 12 in order of rising. You also can see that the houses are not all the same size. The ‘middle of the sky’, i.e. the southernmost part of the ecliptic is not at the 12 o’clock position. The middle of the sky (astrologers call it MC for Medium Coeli) is the boundary between houses 9 and 10.

Let us consider any given point X on the ecliptic. X can be the sun, or a planet or any special point that astrologers consider important. X will rise and set just like the Sun, and we divide the time interval between rise and set into six equal parts. Naturally the time of birth is in one of those parts. If our clock time would be real Sun time, then time of birth would correspond to the position of the Sun. In the given horoscope you can check this out. The Sun is indicated by a little circle with a dot in it. Gauquelin called these parts sectors (not houses), and he numbered these sectors differently from the houses. From rise to set they were numbered 1 through 6 and then from set to rise 7 through 12. So roughly sector number = 13 – house number. So when on a summer day the Sun rises at 4 A.M. and sets at 8 P.M. (no summer time), then the day lasts 16 hours, and on that day the sun spends 160 minutes in sector 1, the next 160 minutes in sector 2 and so on. But after sunset the sectors are only 80 minutes, because the time between sunset and the next sunrise is 8 hours.

The fact that the houses in a horoscope don’t have the same size is related to the fact that times of rise and set depend on the position of the ecliptic. Let’s assume that we are considering a summer day as before. We already noticed that the sun point (which is then at noon in the MC) will spend 16 hours above the horizon. But the ecliptic point that is just rising spends 12 hours above the horizon, and the point opposite the sun will only be above the horizon for 8 hours (the hours that the sun spends below the horizon). On the imaginary movie of subsequent horoscopes one would see the house boundaries and the MC swing back and forth.

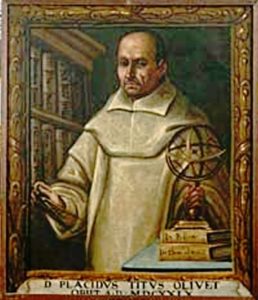

Of course this system doesn’t work if point X doesn’t rise or set at all. This happens inside the polar circles. Placidus (actually Placido de Titi) lived 1603-1668, in a time that it was known that there are places and times where the sun shines at midnight. His calculations don’t work there, but apparently he thought this unimportant.

Of course this system doesn’t work if point X doesn’t rise or set at all. This happens inside the polar circles. Placidus (actually Placido de Titi) lived 1603-1668, in a time that it was known that there are places and times where the sun shines at midnight. His calculations don’t work there, but apparently he thought this unimportant.

Gauquelin’s first problem was his definition of ‘just after’. He used sectors. One might think that he had no choice as this was the only way one could do it in astrological terms. But it did complicate matters. Day sectors in summer are twice as long as the night sectors, and in winter the situation is reversed. But these effects don’t cancel for two reasons. In the first place, the times of birth are not uniformly distributed over the day, and in the second place the number of births goes up and down over the year. This would produce for a ‘planet’ like the Sun a sizable effect, and likewise for planets that are always seen in the direction of the Sun, such as Mercury and Venus. This annual fluctuation is nowadays not so strong anymore, but in the 17th century the French countryside had seven times as many births in March, compared to June, and in December there was another big dip (no doubt the effect of Lent and harvest time on conceptions). Those differences became less pronounced in the course of the centuries. The dip in December vanished, but in the 19th century the number of March births still was twice the number of June births.

‘Planet’ Pluto presents another problem. Pluto takes about 240 years for a full orbit. So Pluto stays about 60 years in the region of the ecliptic where the Sun is in (Northern) summer. If your group of professionals is mainly born in those sixty years, you’ll get a large number of births in sectors 1 through 6.

An extra problem is the fact that these daily and annual rhythms are not constant in time. We have seen this for the annual rhythm, but it holds for daily rhythms as well

Computational errors

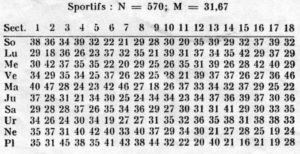

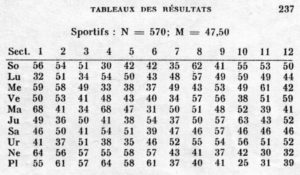

Gauquelin gave tables for ten occupations: medical doctors (two tables), sportspeople, military people, three types of artists: painters, sculptors and actors, scientists, priests, members of parliament and criminals. Moreover, he listed for the same people what their distribution would be if one used 18 sectors rather than 12. As an example I reproduce here the table for sportspeople. He followed his tables with 100 pages containing all names with their birth places and birth times. Only the criminals were omitted.

I went over Gauquelin’s data. I discovered quite a few errors. Small counting errors or maybe typos. Also it seems that Gauquelin doesn’t quite understand the difference between the ecliptic (the Sun’s path between the stars in the course of a year, and the daily path of a ‘planet’ across the sky. He also refers (p. 77) to the well known discoverer of the laws of planetary motion by the name of Kléper (in France this man is also sometimes called Jean Képler – as if to hide the fact that he was a German). Maybe it’s a typo, because on p. 57 there is a Képler in a footnote. This is important, because doing astrological computations without understanding what you are doing can lead to all kinds of mistakes.

When you combine the sectors of the 12 sector system two by two, you have to get the same six numbers as taking those of the 18 sector system three at a time. More precisely, taking sectors 2&3 of the 12-sectorsysteem together, gives the same result as sectors 3&4&5 of the 18 sector system. This is because in the 18 sector system the rise of a planet is in the middle of sector 1. I have checked whether the 18 sector tables were consistent with the 12 sector tables. They are.

The author says that he is listing 570 sportspeople. However the Uranus numbers add up to 568 and the Neptune numbers are 572 together. Also the top row (Sun) produced 571 in the 18 sector table. Of this kind of errors there are more. The Mercury row in the Actor’s 12 sector table is 10 short.

Which ‘effects’?

I have examined this unappetizing number jumble. It turns out that the difference between sectors 1 through 6 together (the sectors above the horizon) and the sectors 7-12 together (the sectors below the horizon) is very large for the outer planets Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. So I won’t consider these anymore. In the priest’s table the ‘inner planets’ Sun, Mercury and Venus are also poorly balanced. The root cause is of course that many births take place between midnight and sunrise. Why this would affect priests most strongly is hard to tell without knowing the social demographics of priests. The second group of doctors and also the group of criminals show this effect to a lesser degree. Several occupations lack this inner planet effect, but I don’t know why.

The only other rows that show a striking effect are the Mars rows of the sporters and the second group of doctors.

‘Immediately after rise and culmination’ was translated by Gauquelin into: sector 1 plus sector 4. When we focus on the sum of these two, the sportspeople show a strong effect. In the 12 sector table shown, one sees a sum of 136 (is 23,86% of 570). Crude computation gives an expectation of 95 (1/6 of 570). Gauquelin took astrodemografic effects into account and arrived at an expectation of 98 (17,2%).

Other tables also show exceptional values for the sum of sector 1 and 4.

However, taking all tables together yields a global Mars percentage of 18.2 percent. Taking this as the norm, only the sportspeople really stick out. The doctors (233 out of 1084) seem to score also high, at least according to modern statistical conventions. But we should also take into consideration that we are looking at ten results. That one of ten results scores accidentally a bit higher is not really very special. The painters (127 out of 906) score very low, and that’s statistically significant (p=0.0009 two-sided), even taking into account that we are selecting the most extreme result of ten. It is not so clear how to interpret all of this. You might draw the conclusion that several astrodemographical factors cause much more variation in the results than the situation of drawing black and white balls from well-mixed vases. The most you can say is that the probability of a birth in Mars sector 1 or 4 is influenced by other factors than the known astrodemographic effects.

Are there other planets with such effects? Not according to me. Saturn yields deviations with doctors and painters. The deviation of the painters is also not statistically significant if you take into account that you are looking at 10 occupations and 7 planets. For the same reason the data of the combination politician+Neptune hardly seem special.

Gauquelin had started with a first batch of 576 doctors. The results surprised him a lot. The claims of Lasson seemed to check out in the case of Mars and Saturn. In order to be able to judge this better, he followed lectures in statistics. All data in L’influence des astres together produce for the doctors a Mars p-value of 0.003. But it is a more or less accidental result among 70 others (7 planets and 10 professions) and possibly more if different ways of grouping the numbers have been tried but not published. If we take that into account, it is not so impressive for an outside observer. Given the fact that Gauquelin was continually testing astrological claims it almost was to be expected that he would meet some kind of fluke some day.

Speaking very generally, if something happens to you that has a small chance of happening when you estimate its probability afterwards, then it is not wise to consider that small chance, possibly in combination with emotional reasons, as an indication that there must be a special cause.

The combination physician-Saturn produced an impressive result in the first batch: 130 (where 96 were expected) out of 576 is quite a lot. But then a second batch yielded 90 (85 expected) out of 598. That is nothing special, so the first result was a fluke. At least that is what a prudent judgment would say.

In 1960 Gauquelin again wrote a book, titled L’homme et les astres. Here he explained that he had observed the same effect among 915 foreign sportspeople, but 599 Italian soccer players and a further 118 lesser known (in France!) German athletes produced nothing special. But rather than considering the hypothesis dead, he conjectured that the sportspeople had to be so good that they had to be selected for a national team to ‘exhibit the Mars effect’.

Now Lasson’s claim was about all occupations, not just sportspeople. Gauquelin’s findings were not much of a confirmation of Lasson’s claim.

The Belgian test

According to Gauquelin, the same effects occurred with foreign painters, but as far as I know, there hasn’t been much interest in that. The Mars Effect for sportspeople drew most of the attention. Gauquelin himself was an avid player of tennis and a bicycle racer, which goes some way into explaining his interest in sports.

Around 1967 the Belgian skeptical committee Comité belge pour l’Investigation scientifique des Phénomènes réputés paranormaux (in short CP or Comité Para) has tried to check the sports-Mars connection.

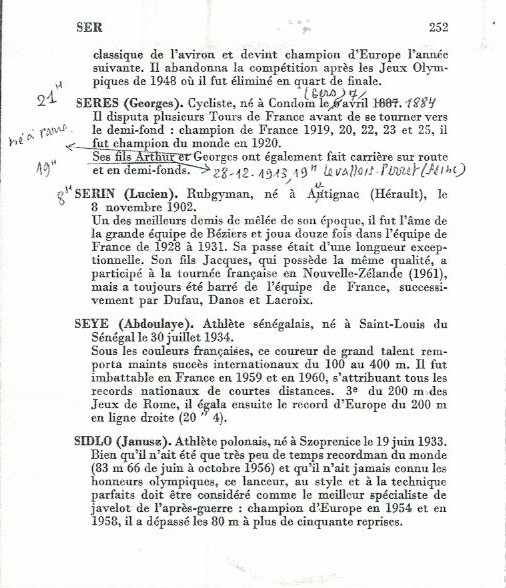

The Committee, I’m sorry to say so, has been conned. For starters, it is a mortal sin in statistics to test a hypothesis formulated on the basis of a certain collection of data, by using the same data. Maybe Gauquelin missed that in his course of statistics, but it is unforgivable for professional scientists. Next, Gauquelin had obtained his first batch of sportspeople from a French sports encyclopedia (L’athlège 1949 and 1950). Already in 1962 he had researched all new names in a then new sports encyclopedia (Seghers), and put their data in his files. When the CP and Gauquelin discussed, they agreed on using just that book of Seghers. Now a test is a kind of bet. I think betting on something you already know the result of, isn’t fair. Third, the Committee added Belgian soccer players. For French soccer players the admittance criterion was that they had been selected at least once to play in the national team. Gauquelin argued that Belgium was so small that the criterion had to be stricter for Belgian soccer players. But he didn’t tell them that he already had obtained the results of a great number of Belgian soccer players, and that he proposed a criterion that would optimize the fraction of players with ‘good’ Mars sectors. Next the CP entrusted the collection of French data to Gauquelin. He had to send the letters to the correct municipalities. This meant that Gauquelin was free to send the letters to the correct town if his earlier investigations had noticed that the encyclopedia data were wrong or incomplete – especially if he knew that the champion was born in sector 1 or 4. I reproduce here page 252

of the Seghers encyclopedia as used by the CP to illustrate what was happening. In the margin are the notations of the CP.

The data given for George Seres senior were wrong. Nonethelss they were found. Moreover, the CP also received answers about the sons of Georges Seres senior, even though the encyclopedia didn’t mention their birth date or place of birth. Georges junior is born in Paris, and without knowing in which arrondissement inside Paris almost impossible to trace. Gauquelin apparently wrote to the town Levallois-Perret with the request to send Arthur’s data to the CP. Twenty years later the French committee CFEPP asked birth data of Georges senior from the town of Condom, giving the (wrong) birthdate April 6, 1887. The form was sent back with the remark ‘introuvable’. Now ‘accidentally’ both Georges senior and Arthur had Mars in the good position, so when Gauquelin was given the opportunity to ‘correct’ the CFEPP data he provided the data for these two. Actually Georges junior was in Gauquelin’s files as well, but with sector 12, and Gauquelin did not ‘help’ the CP or the CFEPP with junior.

In 1976 the CP published the final result: of the 535 sportspeople 119 (22.24%) were born in Mars sectors 1 and 4. Had there been 10 less the CP could have remarked that this didn’t significantly differ from expected values. However, the CP now claimed that it could not say how many were to be expected when astrodemographic effects were properly accounted for. I have repeatedly but in vain tried to understand their article. The notation is too confusing (as mathematician I should be used to complicated notations, but I have given up). The idea seems to be that for each sportsperson one has to calculate the chance that precisely on that date (and place?) someone was born in a good Mars sector, taking into account at what time the Mars sectors start and finish on that day and how the daily birth curve is on that day. The sum of all those chances is the expected number. Gauquelin already was in possession of birth data of 25,000 ordinary people and 16,000 well known people, and he already had determined that the small changes in the birth rythm curves over the year hardly made any difference. On the contrary, the CP opined that it was necessary to determine for each year between 1872 and 1945 a separate daily birth curve. So for 1880 you had to figure out the distribution of births over the hours of the day, and similarly for 1920 and all the other 72 years as well. Moreover it is quite possible that the birth curves in big cities differ from those in rural areas or that the birth curves in winter are different from those in summer, but the CP didn’t mention this – as far as I can tell.

It isn’t very hard to produce a crude estimate of the astrodemographic effect. It is mainly caused by the fact that Mars quite often is seen in roughly the direction of the sun. Combining this with the overall daily birth curve the effect is 0.5%, so one should expect a Mars percentage of 16.7% + 0.5% = 17.2% among ordinary citizens. This is what Gauquelin already had estimated in 1955. Whether this is the real percentage can be doubted. In the data of L’influence des astres we get 17.7% if we leave out the sportspeople. Without the painters and doctors we get 17.5%. So maybe this crude estimate of 17.2% isn’t entirely correct, but it is far from 19.4%. But as long as the true astrodemographically corrected base rate is lower than 19.4%, the ‘Belgian’ result of 22.2% is statistically significant. So the objections of the CP seemed farfetched.

Around this time (1976) a discussion raged in the US about astrology, possibly under the influence of an increase of many forms of occultism and superstition. It was the time that Geller became famous. Gauquelin entered into the discussion because he had been attacked by anti-astrologers. The American statistician Zelen (in the Humanist, januari/februari 1976) proposed a method to establish the base rate for the Mars Effect in France. His recipe was: take 100 or 200 arbitrarily chosen sportspeople, find their birth times and dates and then look for the birth times of everybody born in the same place on the same date. This ought to give enough data to get an estimate of the theoretical base rate. The advantage is that you also control somewhat for differences between town and countryside. Zelen said explicitly that both differences in time (i.e. birth date) and place will be accounted for.

Again Gauquelin was trusted with the execution of this project. He started to deviate from the protocol almost immediately. After consulting with Zelen they (Zelen and Gauquelin) decided that 200 wasn’t enough and they agreed on 300. But then Gauquelin took everybody who was born in capitals of provinces, and more specifically also everybody (in his files) that was born in Paris. The reasons were organisational. Villages in the countryside of France are often so small that there is only one birth per week or even less. But if the astrodemographic effect caused by daily fluctuations in birth times works stronger in rural areas compared to big towns, then this deviation from the protocol would lead to underestimating the base rate. It is not clear whether Zelen had agreed on this protocol deviation. Also the Parisian control group of ordinary citizens was taken entirely from the 14th arrondissement of Paris (the other arrondissements didn’t want to cooperate).

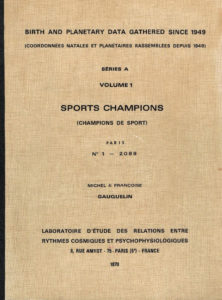

During the discussions of this plan the Americans never noticed that Gauquelin systematically was misrepresenting the nature of his data set. At the time he had been collecting sportspeople, finally reaching 2088. Their data were all in a self-published book of 1970 (see illustration). On repeated occasions he explained that there was an ‘original’ collection of 1553 sportspeople, and after that 535 new ones (collected by the CP), which had constituted an independent and successful test of his hypothesis. So the sample of Zelen should have been taken from this ‘first’ 1553 sportspeople. But that wasn’t at all how matters were. A large number (a bit more than 200) of these 535 ‘new ones’ were in the first batch published in 1955 in L’influence. After that he had continued to collect batches of sportspeople, and for each batch and each sport he had decided after the fact which sportspeople were truly outstanding, and which one didn’t qualify as crème de la crème.

During the discussions of this plan the Americans never noticed that Gauquelin systematically was misrepresenting the nature of his data set. At the time he had been collecting sportspeople, finally reaching 2088. Their data were all in a self-published book of 1970 (see illustration). On repeated occasions he explained that there was an ‘original’ collection of 1553 sportspeople, and after that 535 new ones (collected by the CP), which had constituted an independent and successful test of his hypothesis. So the sample of Zelen should have been taken from this ‘first’ 1553 sportspeople. But that wasn’t at all how matters were. A large number (a bit more than 200) of these 535 ‘new ones’ were in the first batch published in 1955 in L’influence. After that he had continued to collect batches of sportspeople, and for each batch and each sport he had decided after the fact which sportspeople were truly outstanding, and which one didn’t qualify as crème de la crème.

On rereading various old articles about this case I was struck by the repeated assertions of Gauquelin that the 535 CP sportspeople were a brand new sample. But the CP had only chosen the book and stipulated that all sportspeople born in France, and only those, had to be tracked down. In all those discussions no one ever checked how ‘new’ those 535 really were and who had been doing the tracking down.

In my mind Gauquelin seemed to behave like the shopkeeper who surreptiously puts his thumb on the scales when weighing the wares, making them look heavier.

Anyway, when the work was done, the birth data of over 17,000 citizens had been obtained from municipalities, and when the reckoning was done it yielded a confidence interval 16.7%-17.3%, with the theoretical 17.2% inside it.

Such a confidence interval is derived from a random sample. The number 95% means that the computation suggests that 95% of similarly obtained samples would each produce an interval that contains the ‘true value’. Of course the true value isn’t a random variable at all. The numbers derived from the sample are random variables. So it would be incorrect to say that 95% is the chance that the true value is in the interval. No, it is the chance that the interval happens to be such that it contains the true value. The confidence interval is like a hoop that is launched in the direction of small stationary object. The chance is the chance that the hoop is aimed so well that after landing it will circle the object, not the chance that the object lands in the hoop.

When this result of the Zelen test was commented upon, the remark was made that the Mars percentage in the ‘random’ sample of 303 was 22%, just like in Gauquelin’s published database, but that this high rate of 22% mostly relied on 42 Parisians in the total group of 303. That was – in hindsight – a clumsy remark. The question had not been whether the sample of 303 had a higher Mars percentage than the 17,000 ordinary citizens. The question was only: How large is the astrodemographic effect? Or more precisely: is it plausible that an astrodemographic effect makes the base rate 19.4% or higher? The only thing that mattered was: is the sample in matters of birth place and birth date representative of the whole Gauquelin data set. Now there was something not quite right. Gauquelin’s entire data set contained only 4% Parisians, so the Parisians were overrepresented in the sample, just as all big cities were overrepresented and rural areas severely underrepresented. Also, Gauquelin’s 42 Parisians happened to have a Mars percentage of 30% (not significant with a small number like 42) but it smacks of something odd in the process of data collection. However, establishing that the ‘random’ sample of 303 has a higher Mars rate than 17,000 others was never the aim of the investigation.

The article of Abell, Kurtz and Zelen that explains all of this, indeed complains about non-representativity, but it harps so much on these Parisians that I don’t understand that Zelen permitted that he was listed as author. Also Abell knew half a year before the article was published why it was wrong.

The Americans were heavy criticized. They were reproached that they had tried to reason away a result that they didn’t like, namely ‘the Mars Effect exists’. Afterwards they didn’t admit they were wrong. The large effort to get an experimental estimate of the astrodemographic effect was interpreted as an independent new test for the Mars Effect. Later the American organizers were accused of a ‘coverup’ of mostly their own stupidity namely (a) to do this Zelen test at all and (b) to comment on the largely irrelevant composition of the ‘random’ sample. Still later others who understood even less claimed that the Americans had suppressed or changed the data. The critics were right in so far that others indeed thought (wrongly) that this Zelen test was an independent test, see for example the book Implausible Beliefs: In the Bible, Astrology, and UFOs (2008) of Allan Mazur. The main critic was Dennis Rawlins. Unfortunately he was someone who quarreled with everybody, and who was given to uttering wild accusations, riddled with irrelevant expositions and torrents of abuse. The picture here is taken from his sTARBABY, an article in Fate of October 1981. I don’t quite understand why Rawlins was so angry, maybe he thought people people hadn’t listened to him enough.

The American test

The Americans (philosophy professor Kurtz, astronomer Abell and statistician Zelen) decided to perform a new really independent test, with American sports champions. The major part of the organization was done by Kurtz. In this test Gauquelin claimed that only sportspeople should be admitted that were born before 1950. Without any plausible idea about the cause of the Mars effect, he had reached the conviction that the effect vanished in case of unnatural births, namely induced births and cesarean sections. It has the appearance that these Gauquelinian restrictions all were the product of disappointing data collection. I think that Gauquelin himself had been collecting American sportspeople by himself.

The American test’s result was unfavorable for Gauquelin’s hypothesis. All the computations had been done by Rawlins, who later thought he hadn’t gotten enough credit for his work. But then a new light was thrown upon Gauquelin’s modus operandi. He criticized the test because the Americans had failed to select the very very very best. Gauquelin had data of only 31 basketball players in France, who only had 5 rather than the expected 7 in the ‘good’ Mars sectors. This ridiculously small sample had confirmed in him the idea that the Mars Effect doesn’t work for basketball players. (A follower of Gauquelin later even conjectured that basketball was not a form of sport but an art akin to ballet.) Possibly his idea had been confirmed by what he knew about American basketball players. But at the same time he had in his files hundreds of sports flyers. Anyone who knows a little bit about the USA knows that basketball is a national sport, and that it takes a lot of talent to reach the top. Another objection of Gauquelin was that sporters should be ‘international’. That is a strange requirement for a large country like the USA. Gauquelin has collected the data of 216 American sportspeople in a book. This book doesn’t contain many data that had been collected in the US test, rather to the dismay of Kurtz. I suspect that Gauquelin only used data that he himself had collected, with letters still in the original envelopes sent by municipal administrations. But to complain afterwards black on white in public so much about the selection criteria, leaves the reader wondering what he might have been doing in the solitude of his study.

The Americans, especially Paul Kurtz, noticed how the Belgian committee worked. Kurtz then got the plan to organize something similar in the USA. There were plans, but nobody had a clear idea how to organize such a thing. Kurtz had a talent for organization and so in 1976 the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) was formed. The name was almost directly translated from the full name of the CP. Although the CSICOP magazin Skeptical Inquirer published the outcome of the American experiment in the end of 1979, the whole enterprise was well under way before CSICOP was established and CSICOP as organization had no responsibility for the test.

The Americans, especially Paul Kurtz, noticed how the Belgian committee worked. Kurtz then got the plan to organize something similar in the USA. There were plans, but nobody had a clear idea how to organize such a thing. Kurtz had a talent for organization and so in 1976 the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) was formed. The name was almost directly translated from the full name of the CP. Although the CSICOP magazin Skeptical Inquirer published the outcome of the American experiment in the end of 1979, the whole enterprise was well under way before CSICOP was established and CSICOP as organization had no responsibility for the test.

Attempted fraud by Gauquelin

Next (1981) the French popular science magazine Science et Vie published an article by Michel Rouzé (pseudonym of Michel Kokoczynski, 1910-2004) about the American test. This provoked a reaction of Gauquelin with as result (as far as I understood) that a French skeptical organization (CFEPP) set up another test. Actually there was little interest from the French skeptics, but in an unguarded moment someone, maybe Rouzé, had promised to do such a test.

In this test again lots of mistakes were made, especially in the communication with Gauquelin. And again, for the third time the test was about French sportspeople born before 1950. This time the successor of Seghers, namely the sports encyclopedia of Le Roy was used. (The original plan was to ask sports journalists, but they all said: look in Le Roy.) At the urging of Gauquelin L’athlège was used as well. Gauquelin had used the editions of 1949 and 1950, but CFEPP used the 1951 edition.

I want to emphasize that CFEPP put a tremendous amount of effort into this experiment. First the criteria had to be established, then the list of sportspeople whose data were to be requested, then letters had to be sent to the town halls, the exact locations of all these places had to be figured out, and a major part of the effort consisted of volunteers examining the records of all arrondissements of Paris to find out which of the 222 ‘Parisians’ were really born there. But when Gauquelin finally got to see all collected data, he had many objections.

He claimed that Basque pelote (a kind of fives) was international, because it was played in Spain and even in Cuba. So the Basque pelote players should be included. On the other hand rugby was merely a regional sport because it is played only in the southwest of France. (His own files had rugby players from 42 departments, and of course rugby is also played in various obscure and remote English speaking countries around the globe.) Basque pelote was not a regional sport, because Paris had a pelote court. So the standards for rugby were too low. What he didn’t say was that he knew that the few pelote champions had a high Mars rate, whereas the rugby players were somewhat disappointing in this respect.

Worse was that he tried to perpetrate fraud. He proposed corrections and supplementary data that for almost 100 percent supported his hypothesis. He kept mum about the almost equal number of corrections he could have made but that would damage his hypothesis. Maybe he thought that the ‘opposition’ had spoiled his effect by including large numbers of low ranking sportspeople. He complained that Paris was overrepresented with 222 champions. That last point had two causes. In the first place, Paris has lots of good sports facilities, then you almost automatically get more sportspeople. In the second place these encyclopedias often mention Paris as place of birth, when it is actually a suburb of Paris. But all included sportspeople had been either at least national champion or winner in a prestigious international competition, e.g the Tour de France. Actually only sports were considered in which there were competitions, which gave a problem for mountain climbing, as Gauquelin insisted mountain climbing should be included. In the years after World War Two winning in a international competiton was a greater achievement than in the earlier years, because of the increased competition. But this same competition caused less gold medals on the Olympics and less world championships for French. That can create the impression that these young champions weren’t as good as the old ones. But even if Gauquelin really thought that the French skeptics had done something wrong, it is no excuse for cheating. How can we trust anybody who tries to cheat in an important public test?

Next he committed suicide in 1991 (probably because relational problems with his second wife, who had left him shortly before). Gauquelin’s admirers were very disappointed that Gauquelin’s entire archive was thrown out as waste paper. I have asked his ex-wife Françoise why this had happened. She said the apartment had to be delivered empty at short notice. It was filled with filing cabinets crammed with letters from municipalities. I can very well imagine that Gauquelin’s relatives didn’t care for his nonsensical monomaniacal hobby. Good riddance!

A second bias

After the French investigation was completed, the (French) report on it had to be prepared in book form and translated. See the picture. I was asked to check everything thoroughly, which took me about three years of spare time. I got interested and I found a second explanation for Gauquelin’s Mars Effect. The first explanation was that he was all the time selecting who was a worthy champion and who was only a second rater. The second bias starts from the unreliability of the sources. The sources of all the names and places and dates of births often were wrong. This is clear from the fact that in hundreds of cases the town halls couldn’t find the names on or close to the dates given. So it often must have happened to Gauquelin as well that he got an answer from a town hall that didn’t quite agree with the date obtained from the ‘source’. In other words, he selectively threw out ‘unreliable’ data.

After the French investigation was completed, the (French) report on it had to be prepared in book form and translated. See the picture. I was asked to check everything thoroughly, which took me about three years of spare time. I got interested and I found a second explanation for Gauquelin’s Mars Effect. The first explanation was that he was all the time selecting who was a worthy champion and who was only a second rater. The second bias starts from the unreliability of the sources. The sources of all the names and places and dates of births often were wrong. This is clear from the fact that in hundreds of cases the town halls couldn’t find the names on or close to the dates given. So it often must have happened to Gauquelin as well that he got an answer from a town hall that didn’t quite agree with the date obtained from the ‘source’. In other words, he selectively threw out ‘unreliable’ data.

Depending on the answer he then decided whether the information of the town hall was correct or whether he had received the data of a namesake. What I found is that sportspeople who were in a sense difficult to find because of wrong or ambiguous data, the Mars pecentage was quite high when Gauquelin had found them and put them in his files. But when it concerned sportspeople that he must have tried to find, but weren’t in his collection of sportspeople and that had been found by the French skeptics, then the Mars percentage was only 6%.

The French test was planned in such a way that any result would have clearly rejected at least one of the two hypotheses about the Mars rate (17% or 22%). More technically: the level of significance for rejecting the null hypothesis was 2.5% one-sided, with a so-called power of 97.5%. So both parties had a computed chance of 1 in 40 that the test would give the wrong answer even when they were right. In fact the French skeptics ran an unpleasantly large risk that the null hypothesis would be rejected. They had included a large number of champions from the set used to frame the alternate hypothesis. Later they were criticized because it was claimed that the ‘real’ Mars Effect wasn’t at all the 22% of Gauquelin but that it was much less, say 20% or even 18%. So the CFEPP investigation wasn’t the end of the matter. Well, in this manner the affair will never end.

The ‘Mars percentage’ in the last, French, investigation turned out to be 18.7%. A randomizing procedure (randomly reconnect dates and times of birth) produced 17.7% as base rate, which implies a 95% confidence interval of 15.5%-20.1%. If one deletes the champions that were in L’athlège, the Mars percentage is only 16%.

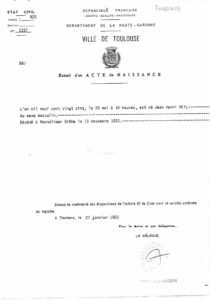

Especially for this article I have tried to count as precisely as I could what the numbers would be if the sportspeople of L’Influence, who served to frame the hypothesis, had been left out. All in all, CFEPP found 1120 sportspeople. Of these 209 (=18.66%) had Mars in sector 1 or 4. Of these 1120 champions 291 were mentioned in L’influence des astres. Of these 63 (= 21.65%) had Mars at the time of birth in sectors 1 or 4. This fact makes clear that the CFEPP criteria were fairly severe on the point of champion quality. Only half of those that were found by Gauquelin in 1955 passed the CFEPP selection. Of course the number of Influence champions that couldn’t be found was quite small, because they had been found already once before. Ninety percent of the Influence champions were found. Of the rest only 72% was found. It isn’t clear why people whose name, place of birth and date of birth were correct in the encyclopedia couldn’t be found. An earlier test in 1983 produced a useful answer from town halls that later stated that they couldn’t find the answer. For example in 1983 Toulouse was able to locate cyclist Jean Rey (29-5-1925), but failed to do so in 1988 (click to enlarge):

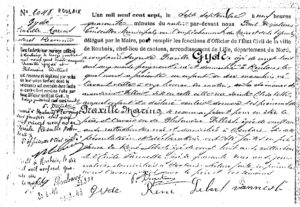

Another example is the case of boxer Praxille Gyde. Gauquelin’s source (L’athlège) mentioned this person with birthdate September 5, 1908. In L’influence des astres we find 5-9-1907. Probably Gauquelin wrote to the town hall of Roubaix and received an answer based on the following document, namely the original birth record, with information about later marriage and decease. I don’t know whether Gauquelin knew and used the correct date when he wrote to Roubaix. When in 1983 a test was done with about 50 names from L’influence to check how town halls respond to this type of request, the question was for the birth time of Praxille Gyde, born 5-9-1907). The town hall returned a photocopy of the birth record (click to enlarge):

This record states that the registration took place on September 7, 1907 at 9:40 and that a male child was presented, which was born l’avant veille à onze heures du matin (’the day before yesterday at eleven o’clock in the morning’) and which was given the names Praxille Marius. But when CFEPP wrote to Roubaix to find out the time of birth of Praxille Gyde, they used the (wrong) date of L’athlège, and below you see the form as returned by Roubaix. After the incorrect birth date it says rien and pas de trace (nothing, no trace found). Note that CFEPP asked for two times: name the time of birth and the time of presentation, in order to prevent officials mistaking the time of presentation for the time of birth. Experience had taught that this happened quite often. (Click to enlarge.)

The high percentage of this group of 291 CFEPP-champions is consistent with the high Mars rate in the original Influence batch. When we leave out these 291 Influence champions the figures are: 829 champions, and 146 (17.6%) with Mars in sector 1 or 4. That is almost exactly the result of the randomizing procedure.

I still don’t understand why CFEPP did not insist on throwing out the Influence champions that had served to frame the hypothesis. But they wanted to be certain that they would find 1000 champions. Their original list had 1439 names, because they had to take into account that they would not receive an answer in many cases. To get more names they would have to lower the criteria for quality, for example not only gold medals for championships but also silver ones. Another possibility might have been to aim for 750 champions rather than 1000.

In fact CFEPP could have calculated around 1983 that 1000 champions and half of them mentioned in Influence, would result in a 1 in 5 chance to find accidentally a ‘confirmation’ of Gauquelin’s Mars Effect hypothesis. That is an unacceptable risk for a test that requires so much work. If we use the actual data (1120 athletes, 17.7% base rate, 291 Influence champions with 63 Mars champions) the chance of an accidental confirmation still was 9% rather than the 2.5% that was aimed for.

One might wonder whether there was a modest astrodemographic effect for the champions that were born long ago, so were mentioned in L’athlège. I tried to count that. There were 237 Athlège champions that were not in L’influence. With 17.7% as base rate one would expect that 47 of them had Mars in sector 1 or 4. With Gauquelin’s hypothesis (22%) one would expect 59. The true number is 54. But the standard deviation with these numbers is 6 or 7, so not much can be said.

I don’t know whether I would have done better than CFEPP. The real mistake was made much earlier, when the Comité Para agreed on an investigation where the hypothesis generating collection was used again. In the discussions around 1980 it was repeatedly stressed, also by the Gauquelins (Michel and Françoise), that the test with the CP was one with entirely new data. I wrote about it in one of the first issues (1.3) of our magazine Skepter, and also didn’t notice it. I only found out while I was preparing an article together with Ranjit Sandhu and Paul Kurtz in Journal of Scientific Explorations, while rereading all earlier discussions and examining closely the list of CP champions.

All in all it seems that the original Mars Effect was an accidental outlier in a not so small sea of random results. The astrodemographic effect seems to be slightly stronger than theoretically predicted, so the CP had somewhat of a point. Conjectured explanations are not difficult to find. In my notes I saw that the CFEPP collection shows a marked difference in birth times between city and countryside. In both cases there is a dip around meal time. But in the towns this dip is in the evening and in rural areas it is between 12:00 and 15:00 with a peak just before that. This may contribute to an astrodemographic effect.

It has the appearance that the discoverer Gauquelin of the Mars Effect and other planetary effects started to believe so strongly that his belief perpetuated itself by various selection effects: who is actually a real champion? are these data absolutely reliable? might an induced birth destroy the correlation? should we take this branch of sport seriously? And finally the originator resorted to fraud when the opportunity rose, and he felt threatened by contrary data.

Two Gauquelin supporters

Geoffrey Dean – an admirer and personal friend of Gauquelin – has launched another hypothesis that should explain why at least some professions showed planetary effects. His article, about 100,000 words (12 times as much in this blog) also appeared in shortened form in Skeptical Inquirer. According to Dean many fathers had made fraudulent declarations in order to provide their new born child with a suitable horoscope. Supposedly these fathers had consulted, in the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, almanacs to find a nice planet in the ascendant or in culmination, and then told the town registrar an incorrect birth time. In my opinion this is rather far-fetched. Supposedly the belief in astrology was widespread at the time (which contradicts statements by others that astrology was quietly fading away at the time; it was only revived by the introduction of newspaper horoscopes). Supposedly the believers thought they could force the stars by lying to the Registrar. And this theory supposes that people attached value to the theory written down in 1945 by Lasson about the influence of the ‘house’ of a planet on a person’s life. Supposedly this custom of astrological lying to the Registrar was so widespread that it produced an effect through the rather weak correlation between parental ambitions and later career of the adult child. Why the effect only worked for the outstanding few in each occupation remained unexplained.

Geoffrey Dean – an admirer and personal friend of Gauquelin – has launched another hypothesis that should explain why at least some professions showed planetary effects. His article, about 100,000 words (12 times as much in this blog) also appeared in shortened form in Skeptical Inquirer. According to Dean many fathers had made fraudulent declarations in order to provide their new born child with a suitable horoscope. Supposedly these fathers had consulted, in the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, almanacs to find a nice planet in the ascendant or in culmination, and then told the town registrar an incorrect birth time. In my opinion this is rather far-fetched. Supposedly the belief in astrology was widespread at the time (which contradicts statements by others that astrology was quietly fading away at the time; it was only revived by the introduction of newspaper horoscopes). Supposedly the believers thought they could force the stars by lying to the Registrar. And this theory supposes that people attached value to the theory written down in 1945 by Lasson about the influence of the ‘house’ of a planet on a person’s life. Supposedly this custom of astrological lying to the Registrar was so widespread that it produced an effect through the rather weak correlation between parental ambitions and later career of the adult child. Why the effect only worked for the outstanding few in each occupation remained unexplained.

When in 1996-1997 the French skeptics’ research was concluded with the publication of a booklet and an article in Skeptical Inquirer, it wasn’t over yet. A German professor of psychology named Suitbert Ertel carried Gauquelin’s torch forward. Already in 1988 he had inspected Gauquelin’s files and discovered a bias. Gauquelin had been rather arbitrarily deciding who was a top sportsman or -woman and who wasn’t, and had introduced a publication bias.

As a matter of fact his files contained 1847 French sportspeople (published plus unpublished) that practiced the same sports as those of the CFEPP-collection, i.e. without air pilots, billiard players etc., and also without people born outside of European parts of France. Of these 349 (18.9%) were born in Mars sector 1 or 4, almost exactly the percentage of the CFEPP-investigation. This suggests that selection was the main cause of Gauquelin’s Mars effect. Throwing away ‘unreliable’ data was of lesser importance.

But Ertel considered it his task to save the honor of Gauquelin. His main idea was that the eminence of athletes should be measured by counting in how many handbooks he or she was mentioned (when Dean published his hypothesis Ertel quickly shot it down; Ertel was quite astute in seeing other people’s errors). Ertel published many articles and a book about ‘his’ eminence effect. In the year 1995 he even wrote in an astrological journal that he thought that by the year 2000 planetary effects at least in the case of famous scientists would be generally accepted as fact.

Ertel’s speciality was torturing data until they confess. When an article by him in the fringe science magazine Journal of Scientific Exploration proposed another trick to unmask the devious plots of Kurtz and others, I proposed to Kurtz that we write a response: ‘Is the Mars effect genuine?’ Afterwards Ertel also objected to a German translation of my SI article in Skeptiker. I already mentioned my response to that: ‘Ertels “Mars-Effekt”: Anatomie einer Pseudowissenschaft’. If you follow the link there, you get the slightly updated English original, with some supplementary remarks. Skeptiker’s editor-in-chief Edgar Wunder closed the discussion with a contribution of his own – at least that is what he thought. Ertel was so angry about our contributions that he sued Skeptiker. He lost and then appealed. He lost again and then appealed again – and lost a third time. The judges must have been flabbergasted while they were listening to the incomprehensible statistical expositions of Ertel. Ertel had to pay all legal expenses for Skeptiker (50,000 Deutsche Mark), but his insurance paid the bill and presumably also his own lawyer’s bills. Ertel died on February 25, 2017, just a week before his 85th birthday.

These are the main points of the whole story. Was Martin Gardner right when he said that Gauquelin passionately believed in an anomaly he had disovered himself, but which was so strange that it wasn’t worth the effort to check it out?

Passionate belief in one’s own theory is a common phenomenon. Insight in how selective observation can maintain such a belief is always useful, especially when the data seem to be acquired with impeccable methods and if recognized scientific methods are used to analyse them. I think we must admit to Gardner that figuring out what is going on is often a lot of work (in this case it certainly was). So much work indeed that this cannot and may not be part of ordinary science. There is already enough serious science to do.

I’m not altogether objective about this, because I have spent an extraordinary amount of work on it, and it is depressing to think it all has been a total waste of time.

Although Gauquelin had spent a lot of effort to refute astrology, many astrologers grasp at the straws of his theory. They aren’t bothered about absence of any statistical foundation of their belief, and also not about refutations. But just one statistical result that isn’t even related to their usual claims is supposed to prove that their elaborate constructions make sense. In other words Gauquelin wasn’t really an isolated crank. For many an astrologer he was a welcome crutch.

Incidentally, nobody in France seems to be interested in Gauquelin. Kurtz and Ertel, both professors, were quite interested. In the Netherlands there are also some sympathizers, so Gardner was right about the general lack of interest in Gauquelin.

Gardner writes that he couldn’t imagine that a serious scientist could afford to spend time on this. But if one considers Ertel as a serious scientist, that is not altogether true. Actually, almost half a century after Gardner en Truzzi corresponded, serious scientists spend a lot of time in writing research proposals to compete for research money. It requires little imagination to predict the fate of a proposal to study any aspect of astrology. All the same several scientists in France, the USA, Belgium and the Netherlands did put some spare time in it, so I’m not the only one who is crazy.

Skeptics that investigate this kind of things as a hobby have to examine the claims of the cranks seriously. Often things go wrong there.

PS 1. The 570 original sportspeople were actually only 568, that is the number of names in the list. There was one case of a person who wasn’t in sports at all, but confused with a namesake. So 567. These 567 all were in the publication of 1970. But in 1970 there weren’t 136 (23.9%) names with Mars in sector 1 or 4, but only 125 (22%). In 1984 the number decreased again by recomputation. In that year Gauquelin wrote that the total Mars percentage in his files had decreased with half a percent. It cannot be excluded that parts of the explanation for the high Mars rate in 1955 consisted of systematic errors in calculation.

PS 2. August 3, 2017. The text that follows the discussion of the CFEPP results is expanded with a reference to our JSE article.

PS 3. March 9, 2022. In this translation some occasional remarks are added.